Marilyn Havlik teaches biology at Walter Payton High School in downtown Chicago. Sandwiched between Chicago's Magnificent Mile on the north side and the city's oldest subsidized housing development to the south, Walter Payton High School opened in September 2000. By design, the school admits an equal balance of Caucasian, African-American, and Hispanic students, drawing from a broad geographic and socio-economic range across the city.

Ms Havlik's biology curriculum follows a blueprint for teaching in the Chicago public schools, where she has taught evolution for 30 years. Her year in biology begins with an overview of science as a way of knowing, followed by units on chemistry, cell structure, energy relations, and DNA.

Before the Lesson Prior to the gene pool experiment, Ms. Havlik's students learned about the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium principle and the conditions under which it is maintained. The day before the lesson, students read an article on genetic diseases as an introduction to diseases that can be inherited and those that provide an advantage in the heterozygous condition.

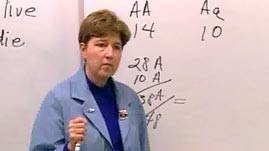

The Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Lesson Ms. Havlik's lesson demonstrates the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium principle by simulating what happens to a gene pool population over time.

After the Lesson After the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium lesson, students were asked to transfer what they learned to new lessons. The class explored data based on the Galapagos Islands iguana, identifying differences in organisms of the same species and developing hypotheses about the relationship between habitat and body characteristics and why the two populations are different. Students were given data on size, feeding habits, and location of the birds. The next lesson explored a finch population over a 10-year period. Students were asked to explain why some finches die and others live. After the genetics unit, the class went on to study mitosis, genetics, evolution, classification, and ecology.

Loading Standards

Loading Standards Teachers' Domain is proud to be a Pathways portal to the National Science Digital Library.

Teachers' Domain is proud to be a Pathways portal to the National Science Digital Library.