If you want to see concrete evidence of evolution, look no further than your hand or your foot. Five fingers, five toes. There's nothing magical about the number, yet five digits at the end of their limbs is a motif that runs through all the animals with four limbs, called tetrapods. Even when there are fewer than five digits in the adult animal -- as in horses' hooves and the wings of bats and birds -- it turns out that they develop from an embryonic five-digit stage. There is nothing inherently advantageous about five digits. Nor is there any environmental pressure that favors five digits on the operating end of four-legged animals' limbs.

Pentadactyly (having five digits) is, in fact, an accident of evolutionary history. All tetrapods descended from a common ancestor that just happened to have limbs with five digits. And over the eons of evolution following that, natural selection worked with variations on pentadactyly rather than starting over again to produce tetrapods with another number of digits, be it two, seven, or 17.

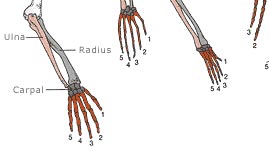

The pentadactyl limbs that tetrapods far and wide all have are examples of homologous structures. The term refers to similarities among species that are inherited from common ancestors. Such similarities are not necessarily functional -- that is, there's no physical reason why the body parts are similar based on the tasks they perform. (When body parts resemble each other for functional reasons, they're called analogous structures.) Critics of evolution argue that species were created separately in their distinctive forms and didn't descend from common ancestors. But the prevalence of the pentadactyl limb argues just the opposite: That for whatever prehistoric reasons, an ancestral tetrapod had five digits per limb, and all of its descendants did as well. The similarity isn't restricted to the ends of the limbs -- the bones of the arm, forearm, and hand of different vertebrates form a recognizable pattern, even though they have been adapted to different functions. And aspects of the nerves, blood vessels, and other tissues in the limb reveal other homologous structures.

Homologies are also seen in other structures, and can even be found biochemically, in the very genetic code that stores information for reproducing individuals. These molecular homologies provide some of the best evidence of a single common ancestor for all life on Earth.

Loading Standards

Loading Standards Teachers' Domain is proud to be a Pathways portal to the National Science Digital Library.

Teachers' Domain is proud to be a Pathways portal to the National Science Digital Library.