Until recently, scientists were convinced that the seemingly infinite variety of life forms that exist must result from an equally diverse set of processes and controls. Once genes were discovered, most scientists believed that these too must be particular to each organism. What we now know is that all organisms -- creatures as different from each other as flatworms and human beings -- have a tremendous number of genes in common.

Genes provide the instructions for building proteins. And many of the genes we have in common with flatworms, or with begonias for that matter, are responsible for building basic proteins. These proteins help control the cell cycle, replicate DNA, build the cell surface, and make nutrients, among other tasks. For many years scientists thought that genes controlled only cellular-level processes. Then along came Walter Gehring and his concept of master control genes.

To most geneticists in the early 1990s, the idea that the same genes in all species controlled processes as complex as eye or leg development was impossibly simplistic. The traditional wisdom was that eyes must have evolved quite differently in different creatures. Insect eyes certainly look different than vertebrate eyes.

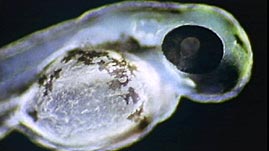

In 1994, however, Gehring stumbled upon a gene in the fruit fly genome that had already been found in the mouse genome. This gene was called the "small eye" gene, in reference to the condition it caused in individuals when it was mutated. Two mutated copies of the gene caused mice to be born entirely without eyes. Surprisingly, the same mutation in this gene had precisely the same effect on fruit flies.

Even though he knew that there are an estimated 2,000 genes involved in making a fruit fly eye, a mouse eye, or a human eye, Gehring began to think of this gene as a sort of master switch for eye development -- the gene that sets the entire process in motion. To test his idea, Gehring tried splicing this master control gene into the part of the fruit fly genome responsible for antenna development. Sure enough, the flies grew compound eyes on the ends of their antennae. Next, he took the eye-development genes out of fruit fly embryos and replaced them with eye-development genes taken from mice. The embryos grew eyes normally. And, as Gehring expected, they grew fruit fly eyes, not mouse eyes -- all because he replaced the control gene, the switch that turns on all the other genes the fruit fly needs to develop an eye.

Since Gehring's revolutionary research, many others have continued the search for master control genes in other species and for other processes. Based on this research, scientists now understand that a very small number of genes are responsible for controlling the development of body plans in all animals.

Loading Standards

Loading Standards Teachers' Domain is proud to be a Pathways portal to the National Science Digital Library.

Teachers' Domain is proud to be a Pathways portal to the National Science Digital Library.