In science, the testing, refinement, and occasional discarding of theories goes on all the time. Even if absolute truth is out of reach, increasingly accurate approximations can be made to describe the world and how it works. Isaac Newton, in setting down his laws of motion, refuted Aristotle's thoughts on the subject -- thoughts that had been widely accepted for nearly two thousand years. But Newton, like all scientists, built on the work of others. Newton studied observations made by the astronomer Johannes Kepler before writing his Universal Law of Gravitation, and his new theory provided a unified explanation of Kepler's diverse and crucial observations.

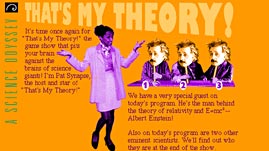

The modification of ideas, rather than their outright rejection, is the norm in science. Albert Einstein knew that Newton's laws of motion worked well in most conditions but realized they broke down when put to extreme tests. So he proposed new versions of the laws to explain the inconsistencies he perceived. And just as Einstein recognized that other people's work could be improved upon, he knew this held true for his own theories as well.

Niels Bohr, who worked on the problem of an atom's structure, is another example of an open-minded scientist who built on the work of others. Bohr worked with Ernest Rutherford's model of an atom, which described the atom as having a small but dense nucleus surrounded by orbiting electrons, and applied Max Planck's quantum theory to explain just how an atom composed in this way could remain stable and not collapse. Bohr added to the understanding of atoms put forth by Newton and Rutherford by developing a model that accounted for some of their most important and illusive properties but that also fit with experimental evidence observed by other physicists over the years. Later, Bohr's ideas were explained by the more comprehensive quantum theory, in whose development he participated.

Loading Standards

Loading Standards Teachers' Domain is proud to be a Pathways portal to the National Science Digital Library.

Teachers' Domain is proud to be a Pathways portal to the National Science Digital Library.