Teachers' Domain - Digital Media for the Classroom and Professional Development

User: Preview

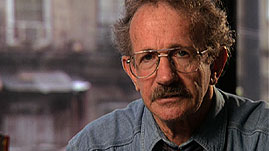

Source: From the WGBH series Poetry Breaks created by Leita Luchetti

In this video segment from Poetry Breaks, poet Philip Levine reads his poem, "Belle Isle, 1949," about a late night meeting and swim that takes place between two strangers. The poem explores themes of connection, boundaries, and where we come from.

Read "Belle Isle, 1949" at the Poetry Foundation.

The title of this poem tells us it is 1949, just after World War II, and we're on Belle Isle, Michigan, an island park near the city of Detroit and the Canadian border. The speaker and his companion seem on the verge of crossing less physical borders—those of experience and adulthood. The poem's first lines, "We stripped in the first warm spring night/ and ran down to the Detroit River/ to baptize ourselves in the brine," immediately suggest this isn't an ordinary swim. Yet the excitement of this section begins to turn when the speaker says this baptism will take place in a river full of "car parts, dead fish, stolen bicycles, / melted snow." The island may be beautiful but its waters are also polluted, ugly—rife with discarded and decaying items that have outlived their usefulness. Despite the warm night, it is cold.

The second section of the poem identifies the "we" as the speaker and a "Polish highschool girl/ [he'd] never seen before." Holding her hand as they go in the water, he notes, "the cries/ our breath made caught at the same time/ on the cold." At this moment the two are united, moving together and sharing a voice. His description of her as a "Polish highschool girl" suggests they are from different worlds, but perhaps on this spring night borders will be crossed.

Within this very sentence, however, the two start to separate. She breaks the surface after him, and the already moonless sky is now starless. In place of celestial light, the speaker sees the "the lights/ of Jefferson Ave. and the stacks/ of the old stove factory unwinking." The abbreviated street name is a clipped, somber contrast to the more languid word "avenue." The smokestacks, which could have been winking suggestively, are as lifeless as well. In this second section, the island—no longer referred to as an elegant "isle"—vanishes. Looking back, the speaker notes, "a perfect calm dark as far/ as there was sight" and then a new light, from a boat or "smokers/ walking alone" on the shore. This new light calls the swimmers home, and the paradoxical image of smokers (plural) walking alone (singular) hints that the boy and girl may soon part.

In the final section of the poem, the couple returns "panting/ to the gray course beach/ we didn't dare/ fall on." They have shared a moment and are out of breath. Yet instead of finding romance, of becoming more than a nameless boy and "a Polish highschool girl," they dress "side by side in silence/ to go back to where we came from." The promising "we" of the first line has vanished. An opportunity has slipped away, and lines that could have been crossed have been redrawn.

Read a biography of the poet Philip Levine at the Poetry Foundation.

Loading Standards

Loading Standards