Teachers' Domain - Digital Media for the Classroom and Professional Development

User: Preview

Picturing America is a project of the National Endowment for the Humanities, carried out in partnership with the America Library Association, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, and the Office of Head Start.

Funding for the educational resources in this collection was provided by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

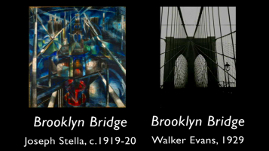

The Brooklyn Bridge was hailed as a marvel of American engineering ingenuity. When it was built in 1883, its two towers were the tallest structures in the Western Hemisphere. Photographer Walker Evans turned its bold form and sweeping lines into a classic American image, both an icon of modernity and a monument that belongs to history.

To Joseph Stella, this structure was the “shrine containing all the efforts of the new civilization of America.” His Futurist rendition of the Brooklyn Bridge was inspired by a night alone on its promenade, surrounded by New York’s noises and pulsating colors, feeling both hemmed in and spiritually uplifted by the city.

Joseph Stella: The Brooklyn Bridge, c. 1919-20 (Document)

Walker Evans: The Brooklyn Bridge, 1929 (Document)

Guide your students in a close reading of the informational texts provided with this video. Download Joseph Stella: The Brooklyn Bridge, c. 1919-20 and Walker Evans: The Brooklyn Bridge, 1929 and make copies for each student.

Begin by having students read the essay silently. Next, read the essay aloud to the class and have students follow along.

Direct students to refer to the text as they answer the questions below.

A Close Reading of "Joseph Stella: The Brooklyn Bridge, c. 1919-20"

A Close Reading of "Walker Evans: The Brooklyn Bridge, 1929"

-----

Visit the NEH Picturing America website to find more innovative ways to integrate works of American art into your teaching.

JEFF ROSENHEIM (CURATOR, METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART): It’s our great cathedral, this Gothic masterpiece. It soars into the sky. It’s grounded into the river. From Brooklyn to Manhattan, it connects these two huge cities. Cable and stone and reach and gesture. It’s a piece of ballet. It’s art itself.

RED GROOMS (ARTIST): I had a marvelous, romantic experience on the Bridge, and that was where my wife and I had one of our first dates. I was trying desperately to show her the most spectacular thing I could to impress her, so we took a walk on the Brooklyn Bridge; it was great. We had a marvelous kiss on the Bridge, and we’ve lived together ever since.

ROSENHEIM: The Bridge itself was just the beautiful thing that was attractive to poets, to painters, to photographers, to filmmakers, and to just everyday citizens. It was a vernacular form that had come from the 19th century, and yet still, in the late 20s, was this powerful, modern image.

This is the coming-of-age story for Walker Evans. It’s the beginning of a career when Evans began this project to photograph the thing that was the largest work of art in his world which was the Brooklyn Bridge. Evans believed in the medium of photography, that seeing was a creative act. The power of black and white, which really is about edges, and this compression of tones, it’s this sort of formal assessment of the engineering structure and how it looks and how you imagine your experience there. He allows us into the picture. It turned out that he would be the great photographer of his generation.

GROOMS: I came here, I officially mark, in 1957, as a new person in New York, not being born here. You know, I particularly liked the set of, well actually cornball, almost iconic things. I’m sure that the Brooklyn Bridge was something I needed to see. I was so into Joseph Stella and his Bridge painting, in 2004 I did the Joseph’s Bridge. I, as an artist started in the 1950s, was steeped in his work and thought he was the greatest. I thought he was one of our great American artists, because in that day, as opposed to now, it’s an interesting thought, New York was still very much the chief subject of even the most sophisticated artists.

ROSENHEIM: Stella’s great painting, which at the time was in the Brooklyn Museum, it’s a great colorful, sort of cubist study. It’s kind of a stained glass window. It’s very modern, very intensely painted. It’s another voice, a voice of the architecture, a voice of America, a voice of the spirit.

GROOMS: For a long time, I thought, well, would this be appropriate if I call it the Joseph’s Bridge? Is it right to him? I don’t know why it wouldn’t be, but is it? I think at one point I was trying to figure out how I was going to add that sort of a vortex-like fragmentation—I wanted to get into that even know I’m not exactly known for that. Both the dimension and the flatness are in our minds, actually. And I must say, that Stella was a deep thinker, he’s way, way into his head there—it probably didn’t seem flat to him either.

ROSENHEIM: The Brooklyn Bridge, like the best of architecture, it’s frozen music, and as a visual form of ambition, it’s a symbol.

Loading Standards

Loading Standards