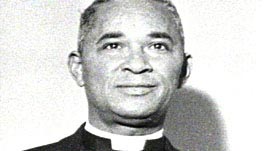

Reverend Joseph Armstrong De Laine grew up in rural Clarendon County, South Carolina. He worked as a laborer and dry cleaner to pay his way through Allen University, an African American college in nearby Columbia. He earned his bachelor of arts degree in 1931 and later went to seminary. De Laine returned to Clarendon County to be a minister and public school teacher. In these positions, he became both a respected leader in the community and an ardent advocate of equal rights and social action. By 1943, he was the president of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Clarendon County, like many areas of the South, legalized segregation in all public facilities, from restrooms to classrooms. As a teacher for 17 years, De Laine witnessed firsthand the racial inequalities in South Carolina's black schools. For example, Clarendon County spent four times more money on white schools than on black schools. Most black schools in the county were dilapidated and overcrowded, and black teachers were paid less than white teachers. While the 2,000 white students in the county had buses, the 6,000 black students had none and frequently had to walk several miles to the nearest black school.

In the late 1940s, De Laine encouraged African Americans Levi Pearson and Harry and Eliza Briggs to petition county officials for buses. The petition was denied, but De Laine and the NAACP persisted. In 1950, 20 plaintiffs sued for better schools and equal education. In 1951, a federal three-judge panel ruled in

Briggs v. Elliot that black schools were unequal to white schools and therefore unconstitutional. The court ordered the schools to be made equal, but did not address the issue of desegregation. One justice, Judge J. Waites Waring, wrote a dissenting opinion arguing for school desegregation.

While De Laine was a respected leader in the black community, his ideas and actions were considered radical and provocative to a white community in which the Ku Klux Klan still beat and lynched African Americans who challenged the status quo. By 1950, De Laine's house had been burned to the ground, and he and his two sisters had been fired from their jobs. Others involved in the case were fired, harassed, denied credit, and refused service in local stores.

However, De Laine's efforts had far-reaching consequences. The lawsuit was eventually joined with four others to form the famous 1954 case

Brown v. Board of Education, in which the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

To escape the arrest warrant and death threats that stalked him in South Carolina, De Laine fled to Buffalo, New York, where he started a new church. Judge Waring, who sided with the black plaintiffs, was forced out of South Carolina by the state House of Representatives.

Loading Standards

Loading Standards