Teachers' Domain - Digital Media for the Classroom and Professional Development

User: Preview

Source: The Human Spark: "Brain Matters"

Major funding for The Human Spark is provided by the National Science Foundation, and by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Additional funding is provided by the John Templeton Foundation, the Cheryl and Philip Milstein Family, and The Winston Foundation.

ALAN ALDA (NARRATION) The video’s narration sometimes makes sense…

PINGU A baby penguin swings on that door.

ALAN ALDA (NARRATION) And sometimes it doesn’t…

PINGU The truck goes up and down in the papers over hills.

ALAN ALDA (NARRATION) The electrodes are recording where and when my brain reacts to these mistakes. When the mistake is simply a word that doesn’t make sense…

PINGU Pingu turns up the penguin really loud. ALAN ALDA (NARRATION) An area in the back of my brain, mostly on the left, reacts within two tenths of a second. But when the mistake is grammatical…

PINGU The concert are starting.

ALAN ALDA (NARRATION) My brain pounces on the error within one tenth of a second, and this time in a region toward the front and exclusively on the left.

Following me into the video booth, and equipped with a much more fetching hat, is six-year-old Donica. When there’s a mistake of meaning…

PINGU Pingu claps her ball happily.

ALAN ALDA (NARRATION) Her brain, just like mine, reacts in two-tenths of a second. But when the video says something grammatically incorrect…

PINGU The pancake falls onto their his head.

ALAN ALDA (NARRATION) Her brain is slower to respond than mine, and the response isn’t so focused over that area in the front left. In fact, Helen Neville argues, it takes perhaps ten or fifteen years for the brain to organize itself to process grammar swiftly and efficiently in just one focused, specialized region.

HELEN NEVILLE It looks for example like that’s an important area for sequencing different kinds of information and of course sequencing is an important part of language. It looks like areas just behind there are very important for tool use in the left side as well.

ALAN ALDA Tool use?

HELEN NEVILLE Tool use, yeah.

ALAN ALDA Tool use over where language is taking place?

HELEN NEVILLE Actually, it’s possible that one aspect of language is closely tied to tool use, especially this kind of action planning and sequencing that we have to do in order to talk.

ALAN ALDA (NARRATION) To find out how closely language and tool use are linked in my brain, it’s time for me to go back into the MRI machine. I’m at the University of Oregon again, where a research team is trying to find out why humans are so naturally adept at using tools.

SCOTT WATROUS Doing all right so far? Alright, so I’m going to give you the gripper in your right hand now…

ALAN ALDA (NARRATION) The plan is for me to use a tool – or actually to imagine I’m using a tool – to perform a task I’d learned just a couple of hours before.

SCOTT FREY OK, Alan, now the fun begins. We’re going to scan your brain while you’re making judgments about how to grasp those objects with your hand or with that new tool that you learned how to use earlier. And we’re going to be looking to see where those patterns of activity are.

ALAN ALDA (NARRATION) Because my upper body is not supposed to move in the scanner, I’m pressing foot pedals to signal which side of the knob I would grasp with my real thumb or the gripper thumb. And even though in each case my arm and hand would actually move very differently, the areas of my brain that light up are the same. While using the tool, my brain treats it as an extension of my body, and is actively planning the muscle movements that manipulating the tool requires. All this tool use planning is going on in the left side of my brain – and very close to the areas we use for language.

ALAN ALDA The fact that they’re so close together, the speech production and so much of the planning over here, is that significant, do you think?

SCOTT FREY It could reflect the fact that there are some common underlying processes. So for example, a candidate I would suggest, at least worth considering, is this ability to adjust a behavior that’s happening right now, in anticipation of a goal we want to achieve in the future. For example if you were to say the word “tulip,” versus the word, “ticket.” Watch what your lips do when you say “tulip.” You start to anticipatorily round your lips during the “T” in anticipation of the vowel coming behind it. Watch what you do when you say the same consonant, “T” in the word “ticket.” “Tulip.” “Ticket.” “Tulip.” “Ticket.”

ALAN ALDA I’m starting to make way for the “oo” in “tulip” even as I’m saying the “T” but in “ticket” I don’t do it. So that’s a clue that there’s some kind of planning going on.

SCOTT FREY You’re planning ahead.

ALAN ALDA And when chimps say “tulip” they don’t do that?

SCOTT FREY As far as we know.

ALAN ALDA (NARRATION) So here I am, in the brain scanner at MIT, to see how hard the machinery in my brain has to work to figure out another person’s thoughts – actually, not so much how hard my brain’s working but what part of it I’m using.

Running the experiment is MIT’s Rebecca Saxe, and a colleague from Harvard, Randy Buckner.

My task is to watch a video of a dog hiding while a girl goes out of the room, then to figure out where she’ll look for the dog when she comes back. When I’m thinking about where dog is, one part of my brain lights up. But to predict where she’ll look I have to think, not about where the dog actually is, but about where she thinks it is.

RANDY BUCKNER There he goes, he got it right.

ALAN ALDA So now, does some other part of my brain light up when I think that other thought, oh wait, she didn’t see it, she doesn’t know?

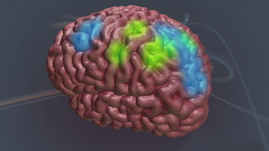

REBECCA SAXE Exactly. So when you’re paying attention not just to reality, not just to where the dog really is, but to her thoughts to where she thinks the dog is, then a different part of your brain is being used. And so that’s what we have a picture of here. This part of the brain is called the right temporal-parietal junction, or RTPJ for short, and that’s the part of the brain we normally see when people are thinking about other peoples’ thoughts.

ALAN ALDA Wait, this is over here?

REBECCA SAXE Exactly. Yeah.

ALAN ALDA (NARRATION) So sitting just above my right ear is a patch on the surface of my brain that that allows me to see into other people’s minds – or at least, wonder about what they’re thinking.

ALAN ALDA Is it any kind of thoughts or is it just me trying to think about the thoughts of another person?

REBECCA SAXE It’s just when you’re thinking about somebody else’s thoughts.

ALAN ALDA Ah. Amazing, huh?

Loading Standards

Loading Standards