Teachers' Domain - Digital Media for the Classroom and Professional Development

User: Preview

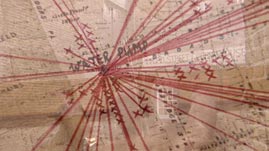

Source: Rx for Survival -- A Global Health Challenge: "How Safe Are We?"

In this video segment adapted from Rx for Survival, actors portray how John Snow, a London physician, traced a major outbreak of cholera in the 1850s to its source. Using logic, statistics, and mapping, Snow rejected the idea that cholera was carried in a cloud of bad air. Instead, he believed contaminated water was responsible for spreading the disease among the local population. Snow’s surveillance and response tactics would become a foundation of modern epidemiology—the science of public health that is built on a working knowledge of probability, statistics, and sound research methods.

Epidemiology is the study of factors that affect public health. One of the central ideas underlying this study is that poor health is not randomly distributed among a population. At first, epidemiology was concerned with epidemics of infectious diseases. However, as it’s practiced today, epidemiology is applied to health-related events that also include birth defects, chronic diseases, obesity, occupational health, and environmental health.

Epidemiologists count cases of disease or injury, define the affected population, and then compute rates of disease or injury in that population. Then they compare these rates with those found in other populations and look for patterns to assess whether a problem exists. If a problem is identified, the data are used to determine the cause of the health problem, how it is being transmitted, which factors are related to exposure, and any environmental factors that may be contributing to the problem. These tactics used to identify and control public health problems are collectively referred to as "surveillance and response."

To identify causal relationships—that is, that an exposure is directly linked to certain consequences, or outcomes—modern epidemiologists use informatics as their tool. Informatics is a field of study that employs technology to improve access to information and how it gets used. In an epidemic investigation, data are collected, sorted according to time, place, and person, and analyzed. The epidemiologist then uses this information to conclude which relationships are causal and how so. Epidemiologists emphasize that most outcomes, whether disease or death, do not spring from a single cause. Rather, they are caused by a chain or web consisting of many contributing factors.

While epidemiology does not seek to prove a causal relationship between an exposure and a health problem, it often provides enough information to support action being taken. Just as a medical doctor may prescribe drugs to treat a sick patient, the epidemiologist may propose a way to end a public health problem and prevent its recurrence in a community. In the case of the video segment, John Snow ordered the handle removed from a water pump that he suspected was the source of the cholera epidemic.

People may not realize that they use epidemiologic information in their daily decisions. When they decide to stop smoking, wear a seatbelt, or get exercise by taking the stairs instead of the elevator, the choices that affect their health may be consciously or subconsciously influenced by an epidemiological assessment of risk.

Loading Standards

Loading Standards Teachers' Domain is proud to be a Pathways portal to the National Science Digital Library.

Teachers' Domain is proud to be a Pathways portal to the National Science Digital Library.