Teachers' Domain - Digital Media for the Classroom and Professional Development

User: Preview

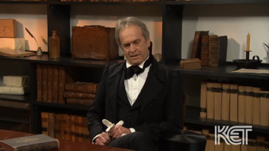

George McGee, a drama professor at Georgetown College and a Kentucky Humanities Council Chautauqua performer, performs a monologue scene as 19th-century Kentucky statesman Henry Clay. In this scene, Clay discusses his stand on slavery, a stance that was both politically and personally troubling to him.

Find additional arts resources for your classroom at the KET Arts Toolkit website.

Henry Clay (1777-1852) was an important and influential 19th-century American political figure. He served as U.S. Senator from Kentucky, as Speaker of the House, and Secretary of State. He also ran for president three times but lost each time. He is often called the “Great Compromiser” because of his successful efforts leading U.S. politicians to reach compromises that delayed the outbreak of the Civil War.

Clay was born in Hanover County, Va., on April 12, 1777. He was the seventh son of nine children born to Reverend John and Elizabeth Hudson Clay. He came to Kentucky in 1797 after earning his law license. He set up a law practice in Lexington. In 1799, he married Lucretia Hart, a member of a prominent Lexington family. His political career began in 1803 when he was elected to the Kentucky legislature. Over the course of the next half century, his political offices would include Speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives, U.S. Senator, and Secretary of State.

Clay ran for president three times. He lost to Andrew Jackson in 1828 and again in 1832. Clay was the leader of the Whig Party, which formed to oppose Jackson. In 1844, he ran for president again, again losing, this time to James K. Polk.

One of the reasons Clay lost the election was his support for the annexation of Texas, where slavery was legal. Voters who opposed slavery did not want a new slave state in the Union.

Slavery, in fact, was a very troubling issue for Clay, as this video segment illustrates. He owned slaves himself. And while he opposed the spread of slavery to the new western states, he did not think Congress had the right to interfere in states where it already existed. Clay supported the gradual emancipation and return of slaves to Africa.

At the same time, Clay felt that, above all, the Union must be preserved. As the United States continued to divide over the issue of slavery, he worked tirelessly to forge important political compromises that forestalled the breakup of the Union. The Missouri Compromise of 1820-21 allowed slavery in Missouri but prohibited it in other areas north of a certain latitude. Clay came out of political retirement in 1850 to help create the Compromise of 1850, which admitted California as a free state but strengthened the fugitive slave law that allowed slave owners to reclaim runaway slaves. This prevented civil war until 1861, nine years after Clay died.

Clay also enjoyed farming. His estate near Lexington was very important to him, and he made important contributions to agriculture as well as to politics. Part of the estate, including a house built by Henry Clay’s son, remains today in Lexington and is a tourist attraction as well as a center for study of this remarkable American statesman.

Loading Standards

Loading Standards