Teachers' Domain - Digital Media for the Classroom and Professional Development

User: Preview

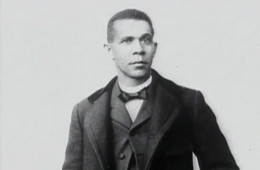

Source: The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow: “Promises Betrayed”

In 1881, Booker T. Washington, then a young teacher, arrived in the town of Tuskegee, Alabama, where he had been invited by local whites to start a school for blacks. He was favorably impressed with the town but somewhat dismayed with the school itself. The buildings consisted of a shanty that was to be used as a classroom with an assembly room provided by a nearby church. The shanty roof was so leaky that a pupil had to hold an umbrella over Washington's head while he taught. To start a school with only a run-down building, a small amount of land, and limited funding was challenge enough. An even greater challenge was winning the confidence of the local white community. But Washington had a genius for reassuring whites that his method of education for blacks would "not be out of sympathy with agricultural life."

On July 4th, 1881 Washington officially opened Tuskegee with what he described as 30 "anxious and earnest students," many of whom were already public school teachers. Washington was the only teacher. As word of the school spread, other teachers and students began to arrive. All were mature men and women. Some were quite elderly. His plan was to train most of his students to be teachers who would return to their rural communities and teach the people how to "put new energy and new life into farming," and also to improve the moral, intellectual, and religious life of the people. With local white support behind him, and his growing ability to secure loans and credit, Washington turned to constructing a new building that would enable him to carry out his goals.

Washington began to raise funds from local people as well as from people in the North for his building. He also had plans to have the students construct the buildings, and by so doing learn the industrial skills necessary to build buildings and other necessary things. He envisioned a school that would teach students everything from sewing, cooking, and housekeeping for girls to farming, carpentry, printing, and brickmaking for boys.

Washington's goal was to have Tuskegee train teachers to work in rural areas, teaching children moral values, personal hygiene, self-discipline, and the virtues of work. He was the foremost advocate of industrial education -- vocational training for blacks. He said: "My plan was for them to see not only the utility of labor but its beauty and dignity. They would be taught how to lift labor up from drudgery and toil and would learn to love work for its own sake. We wanted them to return to the plantation districts and show people there how to put new energy and new ideas into farming as well as the intellectual and moral and religious life of the people." The school was a success and is still in operation today as Tuskegee University.

--adapted from the website The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow

Narrator: Frustrated by the unfulfilled promise of emancipation blacks turned to the next generation, to their children. They believed education would be the key to overcome white dominance. One man would come to symbolize this hope: Booker T. Washington. Born into slavery, Washington had managed to learn to read and write. At nine he worked in a salt mine, but within twenty five years Washington had been a student and teacher at the Hampton Institute and was invited to be principal of a new school in Alabama. That school was Tuskegee.

Narrator: Arriving in a community of farms and sharecroppers, where attending school was rare if at all, Washington faced a great challenge. To build a school, attract students, recruit teachers. On July 4, 1881 in the Zion Hill Baptist Church the Tuskegee Institute was born. Washington and his 30 recruits believed the only way to one day have their own buildings would be to build them themselves.

Margaret Clifford: The reason that it started as an industrial school, was because they had nothing so they had to build, grow and make everything, like harness making because they needed to have harnesses for their farm animals, carpentry because they needed to build the buildings, brick making because they needed to make the bricks. These kinds of trades, printing, shoemaking, tailoring, carpentry all of these things were things they could use to build a business.

Narrator: One student who found opportunity at Tuskegee was a young man named William Holtzclaw. His parents, especially his mother, Addie, were passionate about getting an education for their children. They even built their own school.

William Holtzclaw: I remember my parents went into the forest and cut pine poles 8 inches in diameter, split them in half, carried them on their shoulders to a nice shady spot and built a school house.

William Holtzclaw: There were no floors, no chimneys and the benches were made of the same material.

Narrator: Addie Holtzclaw would provide schemes that allowed William and his brother to get an education for most of the year.

William Holtzclaw: The landlord wanted us to pick cotton. But mother wanted me to remain in school. So she use to out general him by hiding me behind skillets, ovens and pots. Then she would slip me to school the back way, pushing me through the woods and underbrush, until it was safe for me to travel alone.

Lee Holtzclaw: Whenever someone wanted to go to school, they would make sure that one of them would and one would stay at home because if they didn't, the overseer would come around and say, "Where are those boys," and he would get upset. So in order to make sure that didn't happen, she sent one to school and leave one at home to do the work so when the overseer came around and needed some one, he would call them and they would be there.

Narrator: But the limited education was never going to propel the Holtzclaw children beyond the bondage of sharecropping, where if the landowner didn’t cheat you the weather might.

Narrator: William Holtzclaw heard about Tuskegee. He wrote Booker T. Washington a letter.

William Holtzclaw : Dear book. I want to go to Tuskegee to get an education. Can I come?

Narrator: The letter found its way. "Come," Washington replied.

William Holtzclaw: When I walked out on campus I was startled at what I saw. There before my eyes was a huge pair of mules drawing a machine plow which to me at that time was a mystery.

Holtzclaw: There were girls cultivating flowers and boys erecting huge brick buildings. Some were hitching horses and driving carriages while others were milking cows and making cheese.

Holtzclaw: I found some boys studying drawing and others hammering iron, each with an intense earnestness that I had never seen in young men.

Shirley Davis: When he first got to Tuskegee, he was really amazed that there were so many things he didn't know. He was also amazed on how they organized the students in the dormitory setting, particularly himself because he had never slept between two sheets. When he went to the dorm he was sleeping as they say, 'ready roll.' He had all his clothes on and someone had to come in and tell him that you have such a thing as a night shirt and a shirt that you wear during the day.

Booker T. Washington: My plan was for them to see not only the utility of labor but its beauty and dignity. They would be taught how to lift labor up from drudgery and toil and would learn to love work for its own sake.

Booker T. Washington :We wanted them to return to the plantation districts and show people there how to put new energy and new ideas into farming as well as the intellectual and moral and religious life of the people.

Narrator: Washington vision would bear fruit. In less then a decade Tuskegee had over a thousand acres of land, 14 buildings, a farm and a dozen shops from a laundry to a blacksmith with an enrollment of 400 students and 28 teachers.

Narrator: Washington wanted his students at Tuskegee to learn to work and work hard no matter how menial the task. He also wanted to keep Southern whites from feeling threatened.

James Anderson: That's why they thought Booker T. Washington was the great godsend. That somehow he had come forward with an educational philosophy which said in effect, that you can educate a people and still keep them subordinate. And he once gave a talk and a speech, and I think it's the most concrete example. Where he was giving the talk and actually he was asked this question by a white farmer. He said, why should I send Mandy to Tuskegee to learn how to cook when she can spit in a skillet and know whether it's hot? And Washington's response was, the purpose of industrial education is to teach her not to spit in the skillet. Not to teach her to be something other than a cook, but to be a better cook, to be a better sharecropper, to be a better mine worker. And so, whites really thought, this is a godsend. We now come up with a philosophy for education that can keep people in their place and even teach them to be better within their place. And they thought that possible. They learned very quickly that that was not possible.

Loading Standards

Loading Standards