Teachers' Domain - Digital Media for the Classroom and Professional Development

User: Preview

Source: The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow: “Don’t Shout Too Soon”

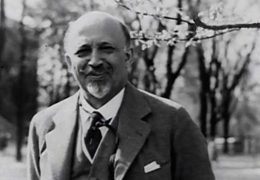

At the end of May in 1925, a deeply troubled W. E. B. Du Bois boarded a train to visit Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, his alma mater. He had been disturbed by reports that Fayette McKenzie, the autocratic white president of the university, had instituted a dictatorial rule on campus. Magazines were censored, dating and dancing forbidden, and conversations between male and female students restricted. McKenzie had been seeking a million-dollar endowment from Northern foundations that were sympathetic to his request -- provided that McKenzie suppress any militancy on campus. The foundation wanted black schools to teach their students to accommodate to Jim Crow as Booker T. Washington had preached, and not to challenge it, as Du Bois was suggesting. On June 2, with the president of the university, the trustees, students, and alumni packing the chapel, Du Bois attacked McKenzie. "I have never known an institution whose alumni are more bitter and disgusted with the present situation in this university. In Fisk today, discipline is choking freedom, threats are replacing inspiration, iron clad rules, suspicion, tale bearing are almost universal."

Du Bois' speech added fuel to the fires of protest that had been burning on campus. In November 1924, the board trustees arrived on campus and were immediately greeted by students chanting anti-McKenzie and pro-Du Bois statements: "Away with the Tsar" and "Down with the Tyrant." The trustees recommended to McKenzie that he make a few minor concessions. McKenzie seemingly agreed then reneged on his promises. Students responded with a brief, but noisy demonstration. The students overturned chapel seats, broke windows all the while keeping up a steady shouting of "Du Bois, Du Bois" and singing "Before I'll be a slave I'll be buried in my grave." McKenzie immediately retaliated by summoning the Nashville police to campus. Eighty policemen armed with riot guns broke down the doors to the men's dormitory, smashed windows, beat and arrested six students. The students were charged with a felony, a crime for which they could be sent to prison.

The arrested students were eventually released and left the school. In response the students called a strike that polarized the Nashville community. Du Bois supported the strike. They held fast for eight weeks despite the pressure. When local white banks and the post office no longer would cash their checks, the black community stepped in to the rescue. Despite having the trustees' support, McKenzie's rule was over and he resigned. The victory had repercussions on other black campuses. At Howard University, a confrontation between the white president and the school's black faculty and student body lead to the president's resignation and the appointment of the first black president of Howard.

--adapted from the website The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow

Narrator: To DuBois, no place was better equipped to train black leaders than his alma matter, Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Established in the 1880's by the American Home Mission Society, it had been for many blacks a way out of the cycle of violence and repression of the South. Fisk had given rise to the first generation of "The New Negro."

James Anderson: Fisk in the 20s is considered the number one black college in America. Students all over are trying to get into Fisk. They were committed to a kind of civil and political equality that challenged traditions, challenged slavery, challenged Jim Crow, challenged the black codes and so forth. And Fisk represented that whole tradition.

Narrator: But in 1924 the white president of Fisk, Fayette Avery McKenzie, would begin a fundraising campaign that would place these traditions at risk. To raise a million dollars McKenzie turned to Southern and Northern philanthropists.

James Anderson: He invited the foundations into Fisk, he pretty much said to them that we will change our ways. We will stop agitating for civil and political equality, we will stop agitating against Jim Crow, against racism in the South. We'll make our peace with the South.

Narrator: McKenzie refused to allow a chapter of the NAACP on campus, and the only version of the Crisis that could be found in the university library was censored.

James Anderson: They began to change the Fisk curriculum. For the first time they began to talk about an industrial education program at what was the quintessential liberal arts institution among the black colleges.

Narrator: In New York W. E. B. DuBois, shocked by what he was told, wrote: "Colored youth must be given a broad vision of truth. My disappointment has continued as charge after charge against Fisk’s policies reaches me."

David Lewis: For DuBois this was a corruption of the ideals and purposes of this institution and the larger objectives of…of intellectual emancipation of people of color.

James Anderson: As the industrialists became more involved in Fisk University, it was clear that Fisk’s most distinguished alumnus was the one person that they didn’t like. And so, they sort of said to Fisk, separate yourself from DuBois.

Narrator: But in 1924, with his daughter graduating from Fisk, DuBois would get the platform he wanted to make his views known.

James Anderson: Fisk had to invite him back. I mean he was, without question, their most distinguished alumnus. His daughter was graduating. Everything seemed appropriate. The students wanted him to come back. The alumni wanted him to come back, so they brought him back. Uh, they should have known better.

David Lewis: And so DuBois came and in that wonderful chapel there at Fisk, DuBois delivered an address which he called Diuturni Silenti, the Latin of which was borrowed from Cicero’s address to the Roman Senate in which Cicero had said, for long years he had been silent, but he would remain silent no longer.

Voice of W.E.B. DuBois: In Fisk today discipline is choking freedom, threats are replacing inspiration, ironclad rules, suspicion and tail bearing are almost universal. The Negro race needs colleges. We need them today as never before. But we do not need colleges so much that we can sacrifice the manhood and womanhood of our children to the thoughtlessness of the North or the prejudice of the South. Ultimately, Fisk will and must survive. The spirit of its great founders will renew itself, and it is that spirit, once reborn, that calls us now. W. E. B. Du Bois.

Narrator: McKenzie had achieved his goal – Fisk had a million-dollar endowment. But, McKenzie had a rebellion on his hands. The students called for a strike.

Jeanne Goodwin: They said they were going to strike and, and just leave the university. So, a whole bunch of them just walked off. They went back home. And I said, well, I can’t follow the crowd. I’m going to see for myself. So, I went over to Dr. McKenzie’s home and talked with him about what his views were. He wasn’t going to change his views. And I told him I was sorry. I enjoyed his children. I enjoyed teaching them in Sunday school. But I was going too...so I left Fisk.

Narrator: Over half of Fisk’s enrolled students walked away rather than live with McKenzie’s autocratic policies. Two months later, on April 16, 1925, McKenzie finally resigned. The students returned victorious. The cherished freedoms they had fought for had been restored. In The Crisis that spring, W. E. B. Du Bois drew his conclusion.

Voice of W.E.B. DuBois: "The fight at Fisk University is a fateful step in the development of the American Negro. It involves the tremendous question as to whether the Negro youth shall be trained as Negro parents wish, or as Southern whites and Northern copperheads demand. Let the attention of no Negro be distracted from this main and crucial point." W.E.B. Du Bois.

Narrator: To Du Bois the fight at Fisk was a lesson in survival. But survival to be what? To do what?

Voice of W.E.B. Du Bois: "The North is no paradise, but the South is at best a system of caste and insult, and at worst a hell. Brothers, come North."

Loading Standards

Loading Standards