Teachers' Domain - Digital Media for the Classroom and Professional Development

User: Preview

Source: The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow: "Fighting Back"

This video from The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow examines the factors that lead to violent and irreparable change in Wilmington, North Carolina. In the years following the Civil War, Wilmington, with a prosperous and growing African-American middle class, was a city that exemplified peaceful co-existence between the races. But in the 1898 election, when the white-dominated Democratic party regained power throughout the state, blacks in Wilmington not only lost their civil rights, but also were victims of a terrible massacre staged by angry white mobs.

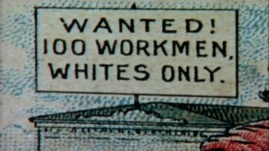

In 1898, Wilmington, North Carolina, located in eastern Carolina where the Cape Fear River enters into the Atlantic Ocean, was a prosperous port town. Almost two-thirds of its population was black, with a small but significant middle class. Black businessmen dominated the restaurant and barbershop trade and owned tailor shops and drug stores. Black people held jobs as firemen, policemen and civil servants.

A good feeling between the races existed as long as white Democrats controlled the state politically. But when a coalition of predominately white Populists and black Republicans defeated the Democrats in 1896 and won political control of the state, angry Democrats vowed revenge in the election of 1898. For many Democrats, black political power, no matter how limited, was intolerable. Daniel Schenck, a party leader, warned, "It will be the meanest, vilest, dirtiest campaign since 1876. The slogan of the Democratic Party from the mountains to the sea will be but one word… nigger."

The Democrats launched their campaign by appealing to the deepest fear of whites -- that white women were in danger from black males. The white newspaper in Wilmington published an inflammatory speech given by Rebecca Felton, a Georgia feminist, a year earlier: "If it requires lynching to protect woman's dearest possession from ravening, drunken human beasts, then I say lynch a thousand negroes a week…if it is necessary." The article infuriated Alex Manly, a Wilmington African-American newspaper editor. He replied by writing an editorial sarcastically noting that many of these so-called lynchings for rapes were cover-ups for the discovery of consensual interracial sexual relations. The Manly article fueled raging fires.

White radicals vowed to win the election by any means possible. Although black voters turned out in large numbers, Democrats stuffed the ballot boxes and swept to victory throughout the state. But in Wilmington, the political victory did not soften white fury. Whites drove all black officeholders out of office. A mob set Manly's newspaper office on fire and a riot erupted. Whites began to gun down blacks on the streets. Harry Hayden, one of the rioters, asserted that many within the mob were respectable citizens. "The men who took down their shotguns and cleared the Negroes out of office yesterday were not a mob of plug uglies. They were men of property, intelligence, culture…clergyman, lawyers, bankers, merchants. They are not a mob. They are revolutionists asserting a sacred privilege and a right." By the next day, the killing ended. Officially, 25 blacks died but hundreds more may have been killed, their bodies dumped into the Cape Fear River.

-- adapted from the website The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow

NARRATOR: Blacks meant to win by legal means. Whites by any means.

ALFRED WADDELL (ACTOR): We shall win tomorrow if we have to do it with guns. If we have not the votes to carry the election, we must carry it by force. If you find a negro voting tell him to leave the poll. If He refuses, kill him.

ROBERT WOOLEY (HISTORIAN): Despite all the intimidation, many, many black voters were turning out and were voting. So the word goes out from Democratic headquarters that if we can’t intimidate the black voters and get a majority that way, we will simply stuff the ballot boxes. And that’s exactly what they do.

NARRATOR: Every black candidate in North Carolina was defeated. But in Wilmington, the political victory did not satisfy white anger. A mob set Manly’s newspaper on fire, and every black official was driven out of office.

BERTHA TODD (V.O.) (WILMINGTON RESIDENT): They could not wait for the time of the change of office to take place.

KENNETH L. DAVIS (V.O.) (WILMINGTON RESIDENT): They decided to take control of everything.

GLENDA GILMORE (HISTORIAN): It was basically a coup. They just took the offices away from the duly elected office holders.

ROBERT WOOLEY (HISTORIAN): So there are no longer any black officials in Wilmington city government.

NARRATOR The coup was followed by a massacre.

REVEREND ALLAN KIRK (ACTOR): Firing began and it seemed like a mighty battle in war time. They went on firing it seemed at every living Negro, poured volleys into fleeing men like sportsmen firing at rabbits in an open field; the shrieks and screams of children, of mothers and wives, caused the blood of the most inhuman person to creep; men lay on the street dead and dying while members of their race walked by unable to do them any good.

GLENDA GILMORE (HISTORIAN): They went after business owners, they went after voters, they went after doctors and black lawyers, those are the people they ran out of town because those were the people they saw as getting out of their place, and therefore encouraging other black people to get out of their places.

NARRATOR: Despite the odds against them, some blacks fought back. Others protested to the federal government.

KENNETH L. DAVIS (WILMINGTON RESIDENT): Blacks from all over the United States wrote letters to the President of the United States begging him to intervene and to stop the violence and the killing in Wilmington.

NARRATOR: In Washington, President William Mckinley remained silent.

JOHN HALEY: I think it showed that the national government had lost its commitment to protecting the civil and political rights of blacks, especially in the South.

NARRATOR: Charles Francis Bourke witness hundreds of blacks fleeing from the city.

CHARLES FRANCIS BOURKE (ACTOR): In the woods and swamps hundreds of innocent terrified men and women wander about fearful of the vengeance of whites, fearful of death. Without money or food, insufficiently clothed, they fled from civilization and sought refuge in the wilderness. In the night I hear children crying and a voice crooning a mournful song.

BERTHA TODD (WILMINGTON RESIDENT): And those of us who were left found our places and stayed there.

NARRATOR: The destruction of black political power in North Carolina unleashed a wave of racial discrimination triumphantly announced in newspapers and printed on postcards. Facilities that were once integrated were now legally segregated- public transportation and parks, restaurants and theaters, jobs and juries. The relative oasis that North Carolina had been for blacks was now a desert of white supremacy.

Loading Standards

Loading Standards