Teachers' Domain - Digital Media for the Classroom and Professional Development

User: Preview

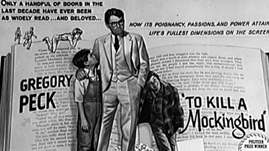

This media asset is from American Masters Harper Lee: Hey, Boo.

For more information on Director Mary Murphy and the Hey, Boo 45-minute classroom edition, visit Mary Murphy & Company.

Summer of ’60

To Kill a Mockingbird was published on July 11, 1960. It was the summer the birth-control pill was released, Elvis Presley returned to civilian life and recorded “It’s Now or Never,” some seven hundred U.S. military advisers were in South Vietnam, Psycho was in movie theaters, "Gunsmoke" was on TV, the Kennedy-Nixon campaign was just beginning, Wilma Rudolph won three gold medals at the summer Olympics in Rome, and Alan Drury’s Advise and Consent, a novel about a secretary-of-state nominee who once had ties to the Communist Party, was at the top of the bestselling fiction list. Better Homes and Gardens First Aid for Your Family was moving quickly to the top of the nonfiction list.

That summer, most forms of racial segregation were not yet against the law, and civil disobedience, such as sit-ins at lunch counters, had only just begun. “People forget how divided this country was,” Scott Turow said. [They forget] “what the animosity was to the Civil Rights Act, which probably never would have been passed if John F. Kennedy hadn’t been assassinated, and it became his legacy. But that was 1963. In 1960 there were no laws guaranteeing that African Americans could enter any restaurant, any hotel. We didn’t have those laws. In that world, [for Harper Lee] to speak out this way was remarkable.” In Alabama only sixty-six thousand of the state’s nearly one million blacks were registered to vote. Three years later, in his 1963 inauguration speech, Governor George Wallace vowed “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever.” Six months after his inauguration, Wallace stood in the schoolhouse door refusing to integrate the University of Alabama.

In Birmingham, where the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church that killed four young girls would become a turning point in the civil rights movement, Andrew Young was working on the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s campaign to desegregate the downtown businesses. “You had, for the first time, black people making union wages in the steel mills,” he remembered. “And they began to build nice homes. These were veterans of service in the military who came back, went to school, got good jobs, and started building nice little homes, nothing fancy, just little three-bedroom frame houses. There were more than sixty of those houses dynamited [by whites in the late fifties]. To Kill a Mockingbird gave us the background to that, but it also gave us hope that justice could prevail. I think that’s one of the things that makes it a great story, because it can be repeated in many different ways.”

Novelist Mark Childress, who wrote Crazy in Alabama, recalled the story of how Abraham Lincoln greeted Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in 1862. President Lincoln reportedly said “So this is the little lady who started our big war.” Childress said, “I think the same can be said of Harper Lee. This was one of the most influential novels, not necessarily in a literary sense, but in a social sense. It gives white Southerners a way to understand the racism that they’ve been brought up with and to find another way. And for white Southerners at that time, there was no other way. And most white people in the South were good people. Most white people in the South were not throwing bombs and causing havoc. But they had been raised in the system, and I think the book really helped them come to understand what was wrong with the system in the way that any number of treatises could never do, because it was popular art, because it was told from a child’s point of view.”

Rick Bragg, a Pulitzer Prize–winning reporter and memoirist, saw the novel’s impact on whites, on “young men who grew up on the wrong side of the issue that dominates this book. They start reading it, and the next thing you know, it’s not just held their interest, it’s changed their views. That’s almost impossible. But it happens.”

One of the reasons it can happen, Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Diane McWhorter suggested, is that “even though To Kill a Mockingbird is such a classic indictment of racism, it’s not really an indictment of the racist, because there’s this recognition that those attitudes were ”normal” then. For someone to rebel and stand up against them was exceptional, and Atticus doesn’t take that much pride in doing so, just as he would have preferred not to have to be the one to shoot the mad dog. He simply does what he must do and doesn’t make a big deal about it.”

--adapted from Mary Murphy’s book Scout, Atticus, and Boo

A Close Reading of the Text “Summer of ‘60”

1. Working individually or in small groups, have students watch the video and answer the discussion questions. Encourage students to share their answers during a classroom discussion.

2. Instruct your students to silently read the background essay, an excerpt from Mary Murphy’s book Scout, Atticus, and Boo. Next, have the students follow along as the text is read aloud to them. Note: Do not access prior knowledge about this subject matter. Instead, let your students discover the meaning of the text on their own (or with a partner). Then, direct your students to complete a set of text-dependent questions followed by classroom discussion. The questions include:

3. Ask students to write two short journal entries that compare the information presented in the video with the excerpt from Mary Murphy’s book Scout, Atticus, and Boo. Tell students to include the following in their journal entry:

NARRATOR: THE CITY OF BIRMINGHAM – 200 MILES HOURS NORTH OF MONROEVILLE WAS AT THE CENTER OF CIVIL RIGHTS BATTLE.

Sound up: - Segregation forever

George Wallace 1963 Inauguration Speech: In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever.

DIANE MCWHORTER : When I started researching my book and I was going through the newspapers looking at the spring of ’63, which was of course when, you know, Martin Luther King came to Birmingham and led the demonstrations that ended up leading to the end of segregation in America. And with the police dogs and the fire attacking the young children and everything. And I was leafing through the newspapers, the local newspapers, and I saw the movie ads for To Kill a Mockingbird and I thought, wow, that’s when that was?

NARRATOR: GROWING UP IN BIRMINGHAM, DIANE MCWHORTER WAS A CLASSMATE OF MARY BADHAM’S. AND SO THE ENTIRE FIFTH GRADE OF THE BROOKE HILL SCHOOL FOR GIRLS WENT TO THE PREMIERE.

DIANE MCWHORTER: I remember watching it, first assuming that Atticus was going to get Tom Robinson off because Tom Robinson was innocent and Atticus was played by Gregory Peck and of course he’s going to win. Then, as it dawned on me that it wasn’t going to happen, I started getting upset about that. Then I start getting really upset about being upset because by rooting for a black man, you are kind of betraying every principle that you had been raised to believe. And I remember thinking that what would my father think, if he saw me fighting back these tears when Tom Robinson gets shot. It was a really disturbing experience. To be crying tears for a black man was so taboo that um, you know. It made me confront the difficulty that southerners have in going against people that they love.

MARY BADHAM: The messages are so clear and so simple. It’s a way of life, it’s a way of thinking about life and getting along with one another and learning tolerance. Racism and bigotry haven’t gone anywhere, ignorance hasn’t gone anywhere. This is not a black and white America 1930s issue. These are issues that are global.

SCOTT TUROW: We may live eventually in a world where that kind of race prejudice is unimaginable. And people may read this story in 300 years and go “so what was the big deal?” But the fact of the matter is that in today’s America, it still speaks a fundamental truth.

MARY TUCKER: the attitudes that were there in the '30s, they have not all changed. So, yes, it is relevant.

Loading Standards

Loading Standards