Teachers' Domain - Digital Media for the Classroom and Professional Development

User: Preview

Source: Produced for Teachers' Domain

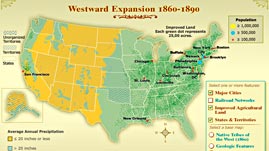

In this interactive map produced for Teachers' Domain, explore several ways in which the United States experienced substantial growth between the years 1860–1890. Population centers, railroad networks, and improved agricultural lands are pictured in decade increments against base maps, reflecting natural barriers to growth and the presence of Native tribal populations.

Just as the Union victory in the Civil War resolved political issues that separated Americans, the technological advances of the previous three decades helped the now reunified United States to function as a nation. The continent's vast natural resources became accessible on a previously unprecedented scale, resulting in growth in established population centers and a wider dispersal of Americans to previously unpopulated parts of the country.

Much of the growth in agriculture reflected the dissemination of inventions from earlier in the century. By 1860, such implements as the reaper (invented 1831), the combine harvester (1834), and the steel plow (1837) had made the cultivation and harvesting of crops significantly easier. The invention of barbed wire (1867), which allowed ranchers to efficiently confine animals to grazing lands, led to similar advances in raising livestock. Agriculture had already benefited from the creation of man-made waterways such as the Erie Canal, which allowed food to be shipped cheaply and quickly; and received an even greater boost from the expansion of railroads, which grew nationally from 20,000 miles of track in 1865 to 70,000 miles of track in 1890.

Nature still inhibited growth in certain sections of the country. Much of the Western portion of the United States, which experiences limited annual rainfall, added relatively little new agricultural activity. Beyond the mountains of the West, farm growth was generally limited to areas that could be irrigated. Limited rainfall and hazardous mountain passes also inhibited the creation of new major urban centers, which continued to cluster in the Eastern half of the continent in the last decades of the century.

Inspired by the heroic image of yeoman farmers, however, both American citizens and new immigrants were moving West in large numbers, undeterred by climate, terrain, or the presence of the Native populations. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 had forced American Indians to leave the Eastern portions of the country for lands in the West ostensibly granted permanently to the tribes. The influx of American citizen and immigrant settlers increased after the Homestead Act of 1862, which gave title to up to 160 acres of federally held land to those who met application requirements and had developed and lived on the land for five years. The number of states and organized territories that emerged on previously unorganized land in the period is one indication of the settlers' impact, as were the numerous acts of exploitation and violence against the Native populations.

Loading Standards

Loading Standards